The Debatable Land #27: The last great British statesman?

David Trimble and the necessary - but difficult - price of peace

Welcome to the latest edition of my newsletter, The Debatable Land. Thanks for being here. If you wish to support my work - and really, ahem, why shouldn’t you? - please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. :-)

Of Peace and Sacrifice

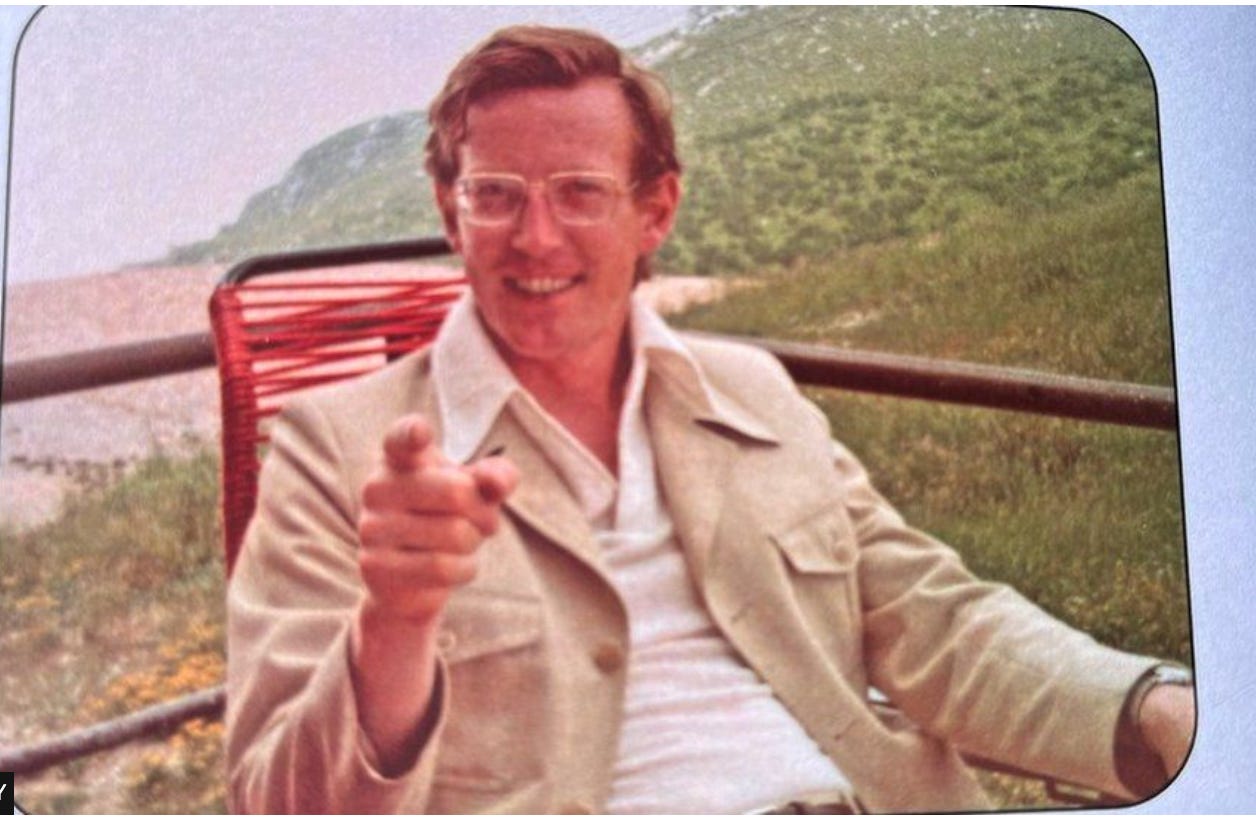

I love this photograph of David Trimble and his family must have loved it too, since it was printed on the order of service for his funeral this week. It is always useful to be reminded that there is more to politicians’ lives than their public persona. Or, at any rate, this is true of the best of them.

And David Trimble was one of the best. An unlikely, even improbable, hero perhaps and certainly the kind who would have scoffed at that label but, in the end, quietly, doggedly, courageously, a hero nonetheless. The United Kingdom has not produced many politicians meriting the title “statesman” in recent years. David Trimble was one of them.

So, there he is, photographed some time in the 1970s and looking like someone who belonged on the Italian rivier…