The Debatable Land #6: In Search of Lost Britain

A strange, mysterious place that's harder to find than you might think...

Hello! I’m sorry this week’s newsletter is arriving rather later than is usually the case. I have been laid up in bed with a dose of covid all week and while I’m much better now it has taken a toll on productivity, largely, I think, because covid saps the mind rather more than - at least in my case - it wracks the body. Still, onwards and vaguely upwards and with luck I should escape covid-gaol on Monday…

The land that wasn’t there

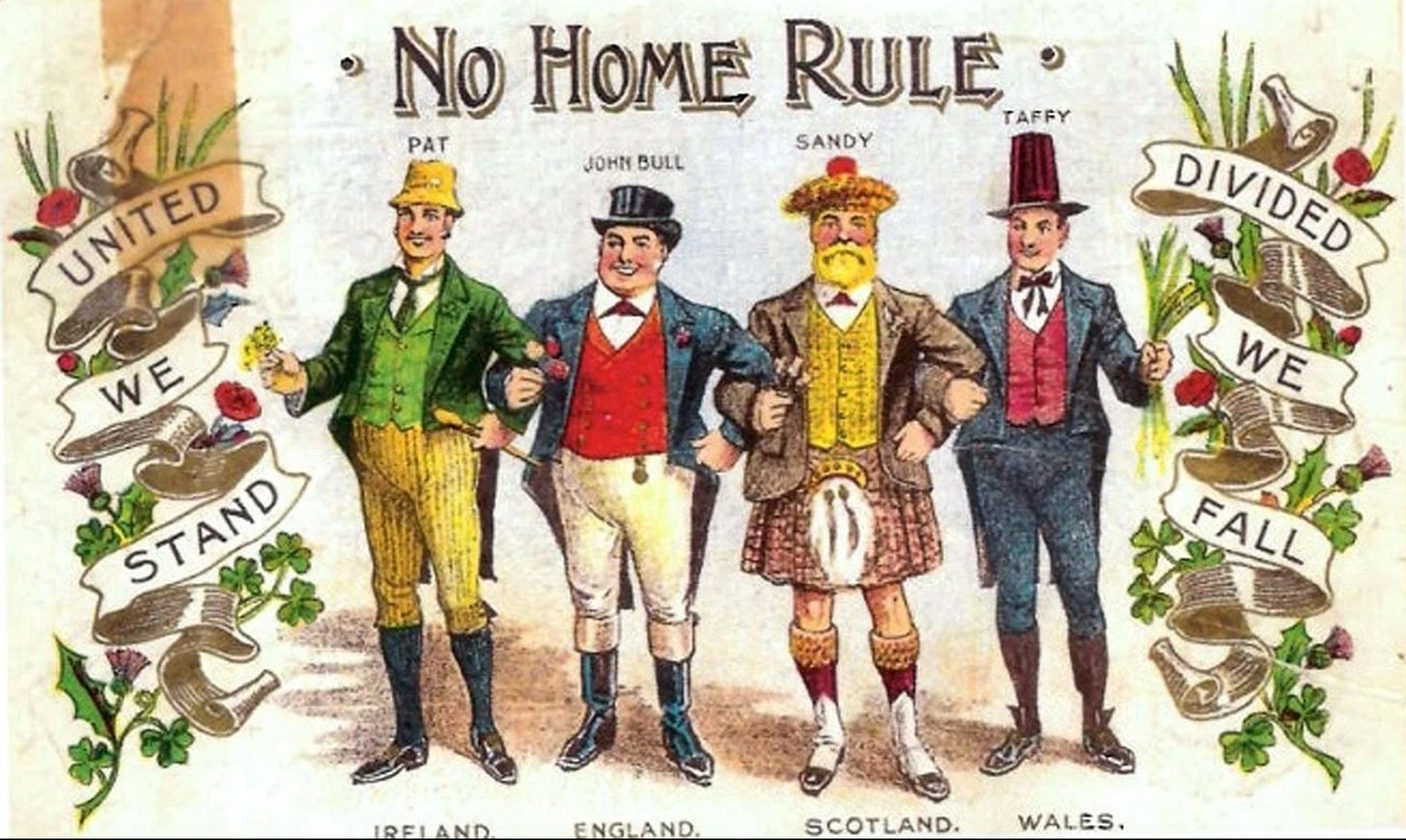

A couple of years ago The Atlantic, that venerable America magazine, made good on the promise of its name by expanding, just a little, into the United Kingdom. It hired Helen Lewis and Tom McTague, each of whom are on my list of writers to “Always read, regardless of subject”. Last week the magazine published an essay written by McTague and gave it the headline: “HOW BRITAIN FALLS APART: A road trip through the ancient past and shaky future of the (dis)United Kingdom”. Aye, aye, I thought, let’s have a look at this.

In truth, McTague’s essay is less a taxon…